Antonelli San Marco

Who: Filippo Antonelli

Where: Montefalco (Umbria, Italy)

What grapes: Grechetto, Trebbiano Spoletino, Sangiovese & Sagrantino

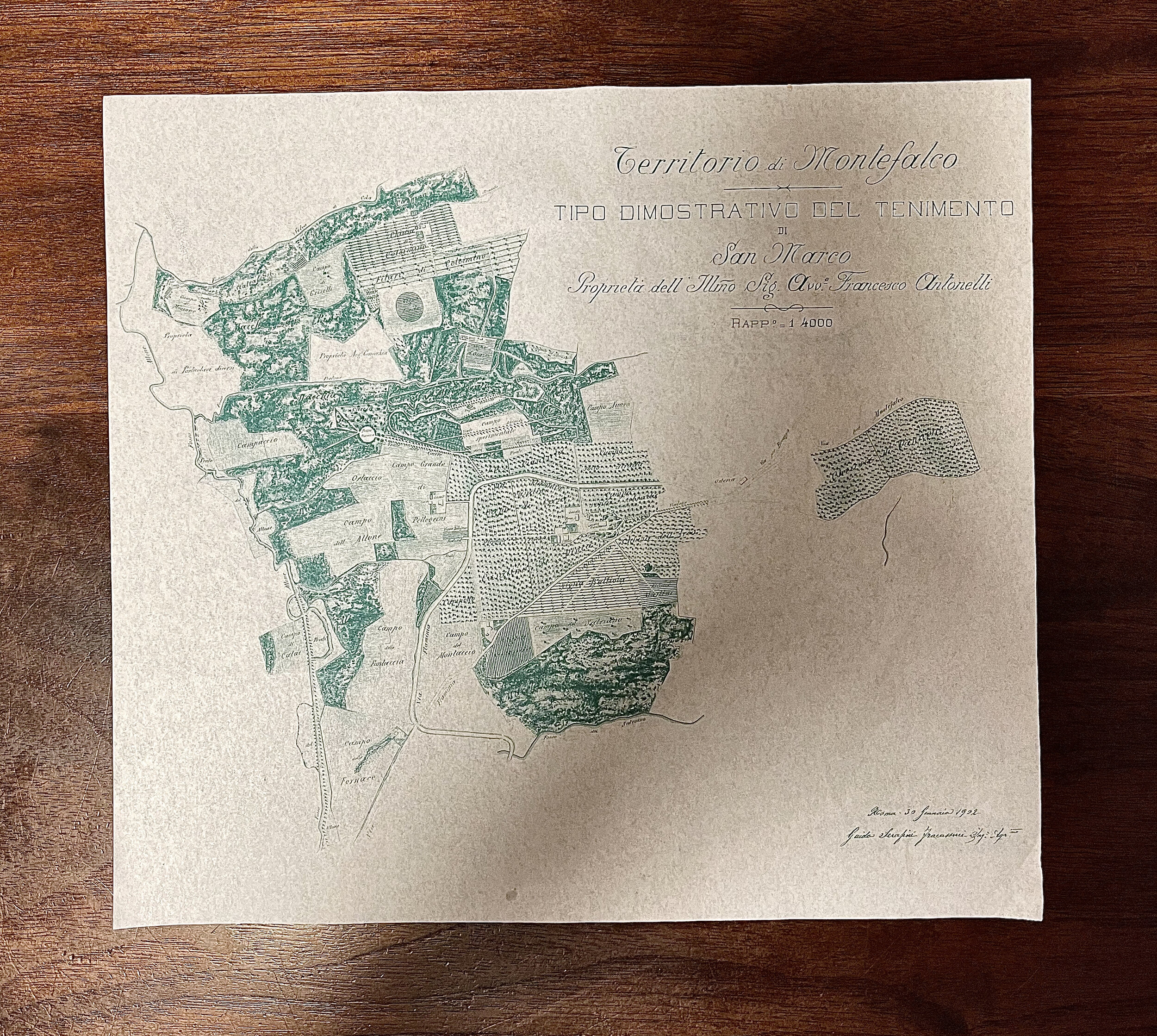

Key facts: a 90 hectare family estate since 1881 completely dedicated to the organic production of vines (50 hectares) and olives (10 hectares).

Website: https://www.antonellisanmarco.it/en/

Instagram: @antonellisanmarco

Antonelli “Trebium” Trebbiano Spoletino Spoleto DOC

Viticulture: Certified Organic

Soil type: Alluvial, Clay, Limestone, Sand

Elevation: 200m - 300m

Grapes: Trebbiano Spoletino (100% from massale selection of the best old Trebbiano Spoletino vines, grown according to the vine training system between maple trees.)

Method of fermentation: The grapes are hand-picked. Skin contact maceration, soft pressing, static cold clarification; fermentation in large oak barrels. It remains on the yeasts for 6 months, it is then bottle-aged.

This is no ordinary Trebbiano. Named after Spoleto, the beautifully preserved ancient town in south central Umbria where this distinct cultivar of Trebbiano is abundant. Quality wine from Trebbiano Spoletino is becoming increasingly common. Italy has taken notice. It’s a fashionable grape there, likely to become increasingly so here, and with good reason. Antonelli’s version smells of white flowers, lemon thyme, and apple. The wine strikes a nice balance. Bright enough, sunny, but also ripe: easy to consume. I like that it’s not at all flashy, but still compelling: it’ll get you interested in a second glass. — JM

Antonelli Grechetto Montefalco DOC

Viticulture: Certified Organic

Soil type: Calcareous clay

Elevation: 450m

Grapes: Grechetto

Method of Fermentation: The grapes are handpicked in the third week of September. Soft pressing, cold static clarification; fermentation in stainless steel tanks. In stainless steel tanks, on yeasts; then in the bottle.

Antonelli “Baiocco” Sangiovese Umbria IGT

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Calcareous clay

Elevation: 300m - 400m

Grapes: Sangiovese

Method of Fermentation: Sangiovese is hand-picked at about the end of September. Fermentation in contact with the skins for about two weeks. Ageing in stainless steel tanks for some months and then in the bottle.

Antonelli Montefalco Rosso DOC

Viticulture: Certified Organic

Soil type: Calcareous clay

Elevation: 300m - 400m

Grapes: 70% Sangiovese, 15% Sagrantino and 15% other red grapes

Method of Fermentation: Harvest begins with Sangiovese towards the end of September and ends with Sagrantino in October. The grapes are hand-picked. Each varietal is separated. Fermentation in contact with the skins and maceration for about 2-3 weeks. Blending of varietals and ageing in large oak barrels for at least 9 months, static clarification in cement vats.

Antonelli Montefalco Sagrantino DOCG

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Clay & Rich in Limestone

Elevation: 300m - 400m

Grapes: Sagrantino

Method of fermentation: Using gravity feed; fermentation in contact with the skins for 25 to 40 days. The wine clarifies spontaneously with no need for filtration. In large oak barrels for at least 18 months. Then the wine settles in glass lined cement vats for some months before being bottled.

Just in time for winter, this iconic estate sends us a small supply of their structured, robust, certified-organic flagship wine. Wonderfully old world aromas: rose, violet, plum, spice. Substantial tannin. Really you should drink it with meat, but if there’s a reason you are avoiding animal protein, I’d pair this Sagrantino with a creamy wild mushroom risotto. With thyme. And Carnaroli rice. — JM

Antonelli Montefalco Sagrantino DOCG 3L

Antonelli Montefalco Sagrantino DOCG Chiusa di Pannone

Antonelli Mar/April 2022, or The World of Filippo Antonelli

Chapter Two: Antonelli San Marco (Monfefalco, Umbria)

Incidentally, it is the season for stalking the wild asparagus in Italy. On the path to Antonelli San Marco dozens of foragers appear from drainage ditches and scrubby hillsides with baskets full of this springtime delight. Tables are set up on roadsides, offering for sale a treat to gourmands too lazy or inept (like me) to find their own tender stalks.

The weather is changing. Filippo Antonelli’s colleague Marco Baldovin greets me at the door of their tasting room with a warning that snow is on the horizon. My time in Lazio was dry, warm, and bright. On the edge of April, it’s ominous to feel a cold wind and dark skies bearing down on northern Umbria.

It does really help with tasting the wines, though. I’d visited Antonelli once before, in July. The Trebbiano Spoletino showed brilliantly. Even inside an air conditioned office, the built-to-last Sagrantino struggled. Or, I struggled with it.

The Antonelli family bought the farm from the Italian government in 1881. It used to be owned by the Vatican. The estate has been certified organic since 2009. Marco says the olive oil they make has always been organically produced. He’s my guide today because he’s a competent and patient source of information regarding the sprawling endeavor. Also because Filippo Antonelli’s daughter is graduating from university in Torino, so the boss is away.

Their property is criss-crossed by walking paths. I’d anticipated using these roads to shake off car fatigue. Driving wind and ice changed my plans. Instead, Marco and I inspected their large and growing cellar. They built the current winery building 20 years ago. It is three levels, and the fruit moves through the stages of fermentation and aging via gravity. Today Antonelli houses over a million bottles underground. The property is large, but more importantly, many wines at this address wait 5+ years to be released. This aging, often in large oak barrel, is essential to reveal the appeal of Sagrantino. Sagrantino is the second most tannic grape in the world.

Antonelli make 12 wines. Buckle up palate, because we’re about to taste them all! Ten of the 12 are fermented in stainless steel. The winery does spontaneous natural fermentations and uses pied a cuvee to culture ambient yeasts from their environment. Most of the aging of the reds takes place in Stockinger (pricey) Austrian barrels, vessels that (on average) are 15 years old. The estate is also experimenting with ceramic small amphora, in a variety of shapes.

Marco says the property could be certified vegan. They use no animal products in the making of the wines. But to be certified vegan requires a large payment to the certification organization, and the winery isn’t sure the expense is worth it. I don’t care about the logo on the label, but it’s good to know they are vegan.

We start our tasting with the sparkling Trebbiano Spoletino. Fresh lemon aromas and white flowers are in the foreground, followed by a faint spice. When Antonelli started farming Trebbiano Spoletino there were four wineries growing the grape. Now there are 39.

The 2020 Antonelli Trebium Trebbiano Spoletino (available in NC) spends six months in wood barrel. It has a lovely mellow texture, and a chalky finish. I’m not ashamed to say I took a magnum of this wine when I left the winery, to serve as inspiration for my travels.

The 2019 Amphora aged Trebbiano Spoletino Anteprima Tondo is tannic, with an amber color. The wine doesn’t take it too far, if you know what I mean. It’s an orange wine that plays nice.

The 2021 Grechetto is aged solely in stainless steel. It’s clean and bright, fun and varietally correct. I’ve been thinking for a year or so that we should import this wine, and tasting it once more confirms this belief.

The 2020 Baiocco Sangiovese Umbria is showing pretty well on this visit. It’s also aged solely in steel. Maybe it’s a tad anonymous, but the fruit is clean and articulate, and there are zero rough edges.

The 2019 Montefalco Rosso is 70% Sangiovese, 15% Montepulciano, and 15% Sagrantino. “It’s the wine that pays the wages,” according to Marco. It has nice clarity and balance. Cherry. Fine tannin. The wine is good. Their wages packets are secure.

The 2018 Montefalco Rosso Riserva is 80% Sangiovese and 20% Sagrantino, aged 18 months in oak. Marco states that the best Sangiovese in the vineyard ends up here, and that the farm only makes this red in optimal vintages. Black cherry aromas dominate, followed by varietally-correct Sangiovese secondary aromas, faint astringency, and some tannin.

The 2018 Contrario Sagrantino is aged solely in steel (!!) Antonelli considers it their “Langhe Nebbiolo” equivalent. Red cherry wafts from the glass. It smells great, but I can’t get past the hard tannin. I want it to mellow in wood. But what do I know?

As I need at this stage to refresh my palate with pork fat, let’s discuss Antonelli’s charcuterie. The pigs on the property only eat legumes and cereals. They get to roam around. They are slaughtered at 18 months old, elderly by pork production standards. This way the meat has more complex flavor, and better texture. They are reddish-brown Duroc pigs, an older breed that’s still common on farms in North Carolina. Antonelli’s pork production is small, but it really makes me wish I owned a meat slicer. I’d fill up my luggage. The prosciutto is aged in the mountains nearby for three years. Salt is the only added ingredient.

The 2016 Sagrantino di Montefalco is more purple in color and flavor. I mean that in a very positive way. Marco thinks it could be the estate’s best vintage yet.

We taste the 2016 Molino di Attone Sagrantino di Montefalco, a single vineyard wine from a site three kilometers from the cellar. The soil in this parcel is richer in minerals. It’s also east-facing. I perceive the wine to be a tad drier.

The 2016 Chiusa di Pannone Sagrantino di Montefalco has a definite chalky cherry character. This single parcel of Sagrantino is south facing. The textural differences between the two wines is striking. This feels riper. Both are excellent.

At the end we try a 2008 Chiusa di Pannone Sagrantino di Montefalco. Now this is much more pleasant. Suddenly it all makes sense. In spite of Antonelli’s best efforts, we are drinking these reds far too young. We need to keep them for over a decade, braise something for hours, and sink into a perfect moment of warm, wintry culinary bliss.

Snapped out of my daydream by gale force winds hitting the winery’s large windows, I re-mask, bundle up, and head out in the direction of Montefalco. Marco quips that climate change brought this extreme moment. “It never used to be this cold in April!” The seasons are all mixed up. While challenges mount, it’s reassuring to see a farm being good stewards of the land, and respecting the foods that the earth provides. A small victory for sustainability.

It’s a large farm that’s a short jog from Montefalco. Over a hundred acres of certified-organic vineyard, set amid 400 plus acres of olive groves, fields of grains, abundant woodland. There’s a cooking school, and a swimming pool.

On a warm July evening Kate Elia and I had dinner with Toni and Aljoscha on the breezy second-floor balcony of their home. Their son William and his partner were there, too, and of course the conversation swirled around our respective current-and-future wine projects. William was planting high elevation vineyards in Chianti Classico, to bolster the work of Corzano e Paterno, or perhaps as a side project. The topic of where we were headed in Umbria came up. I mentioned Antonelli San Marco, in Montefalco. Aljoscha and his son William spoke highly of the winery, and Filippo Antonelli’s role in that DOC. It was clear they both respected him and considered Antonelli an interesting character.

The following day we met Filippo for lunch. The meal was good, the Trebbiano Spoletino was memorable. I left Italy feeling it was the best white wine I drank during the multi-week excursion. Trebium is fermented in large Austrian oak barrels. There’s some skin maceration, and lees contact. At lunch it was golden in color and had ripe orchard fruit aromas. Any skepticism I had of this potential partnership dissipated in the light of its excellence.

Filippo is an enjoyable lunch host, offhandedly informative, wry, understated. Of course conversation centered on Umbria and its cuisine. The region was a papal state, and pork fat was the basis of the cuisine, because olive oil was (and is) a valuable cash crop. Antonelli said cured ham was “invented” in the mountains of Umbria, in Norcia, Perugia. The Romans established a medical school in Norcia that specialized in surgery. Its students practiced on pigs, which were salted and air dried for this purpose. Like Tuscany, Umbria is infamous for its unsalted bread, which was created when the pope doubled the tax on salt and bakers of the region, in Antonelli’s words, “went on strike against salt.” Antonelli’s family have a small cooking school at their ancestral home/manor house, next door to the winery. The stove in their kitchen is a mighty, multi-ton thing, a dream appliance that would dwarf any normal cooking space. Still, I want one.

Sagrantino has been grown in the region since at least the 1500’s. DNA analysis has found no similar grapes in the area. It is distinct. Historically Sagrantino was made into passito. Today the traditional sweet version and fresher, lighter versions are available. Lighter for Sagrantino is still relatively robust.

During the mezzadria there were 7-8 families living within the boundaries of the Antonelli estate. Filippo’s family started making dried grape wine on the farm in 1981. His great-grandfather bought the estate from the church in 1881. Today the property is certified organic.

We stayed there for a couple of days. In the evening the setting is relaxing, a stately old stone country estate on top of a hill, surrounded by vines, with Montefalco a few kilometers in the distance, and a swimming pool nearby. At night the house becomes spooky. Wooden shutters bang, beams creak, the ghosts of centuries-old oil paintings glower. Angular outlines of taxidermied birds of prey cast shadows. A stuffed fox lurks above the fridge, ready to pounce. The dining room is medievally dim. The space seems to consume meagre light. In spite of intense curiosity and (relative) certainty of being alone, there are hallways down which I wouldn’t wander. There’s at least one secret door disguised as a bookcase to the place. A large room stocked with Amaro hides behind it. I bolted the door to my room when darkness fell. The hallway outside was lined with bookcases and photographs of Italians in ceremonial uniforms on campaign in Ethiopia. Compelling and foreign, taken out of time. A small portrait in oil of a man with a moustache stood guard over my bedside table, shifty eyes following activity in the room. It’s windy at night. Shutters bang, indistinct howling sounds accentuate the overall impression that this place is haunted as F…..

Longobard German dukes occupied Spoleto for many centuries. From the autostrada it is architecturally compelling. I’m glad that one of Italy’s emerging white wines of exceptional quality bears the town’s name, and is made in the surrounding hills. I have reason to return, to poke around. Montefalco is a pleasant place to visit, too: hilly, with impressive stone walls and churches, and a large open central piazza. On this first trip Umbria felt vast, and varied. Green.

At the outset of Piedmont Wine Imports I considered it my mission to import the produce of small family-run organic farms. Meeting Aljoscha on my initial wine-finding trip through Tuscany began an evolution of this view. His family farm is large, multi-part, quite productive. At home in America, my perspective shifted through conversations with members of the southern foodways alliance, and farmers in that orbit. If our food system is broken, can tiny farms fix it? Now I see room in our warehouse for the work of larger organic farms, too. Antonelli cultivates over 100 acres of grapes, part of a sprawling wooded 400-acre property. They grow grain, too. It’s a big piece of chemical-free agriculture, at once productive and integrated with the history and natural landscape of Filippo’s homeland.

At a time of polarization in our community, I see value in small start-up wineries run by one or two passionate people. Also, I admire successful, centuries-old family businesses that support dozens of people in their community, and care about sustainability in the ecosystems surrounding their farm. They are allies. There’s no need for false binaries. They can feed each other, by creating larger markets for organic food and wine, and by sparking innovation and change in the global wine community.