CORZANO E PATERNO

Who: Arianna Gelpke and Aljoscha Goldschmidt

Where: Frazione San Pancrazio, north of Poggibonsi, west of Greve (Tuscany, Italy)

What grapes: Sangiovese, Canaiolo, Cabernet, a little Merlot, Trebbiano, Malvasia, Semillon, Petit Manseng, Chardonnay

Key facts: This 40-year-old working family farm makes unpasteurized sheep’s milk cheese, olive oil and wine from fields they own on two sides of a valley. The place is an inspiring integration of man and nature.

Website: https://www.corzanoepaterno.com

Instagram: @corzanoepaterno

Corzano e Paterno “Il Corzanello” Bianco Toscano IGT

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Stony

Elevation: 300m

Grapes: Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Trebbiano, Petit Manseng, Verdicchio, Semillon

Method of Fermentation: A blend of 6 different varieties of organically grown grapes, planted in the cooler areas of the property.

Manually harvested grapes are immediately cooled and processed only at low temperature. Grapes are gently whole bunch pressed and the must decanted for 24 hours. Temperature is controlled during fermentation and maintained between 15°C and 18°C. After fermentation the wine is racked and kept on the fine lees for 4-5 months, it does not do malolactic fermentation. Bottled March following harvest.

Bottles Produced: 27,000

Arianna and Aljoscha are more than farmer/winemakers, they are also wine lovers with an understanding of great wine made elsewhere. This perspective helps make Corzanello Bianco a standout white wine, in a region where the biancos can often taste like afterthoughts to iconic Sangiovese. By planting a diverse collection of varieties and working in field and cellar to capture fresh aromatics and acidity, Corzano e Paterno have made this wine a consistently delicious, compelling, easy-to-love core part of our portfolio. Drink it with anything really, grilled summer vegetables, wild Ottolenghi dishes that lean on lemon and garlic, even simple roasted chicken and couscous. — JM

Corzano e Paterno “Il Corzanello” Rosato Toscano IGT

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Round, smooth stones that were once a seabed

Elevation: 300m

Grapes: Sangiovese

Method of fermentation: The grapes are all hand picked and immediately cooled. Once cooled they are whole bunch pressed and the must left to decant for 24 hours. Fermentation is temperature controlled between 13°C and 15°C for a slow fermentation to preserve aromas. After fermentation the wine is racked from the heavy lees and kept on the fine lees at a temperature of 8°C to prevent malolactic for approximately 4 months. Bottled March following harvest.

Bottles Produced: 12,400

Il Corzanello Rosato is mineral and fine, precise. Exactly what’s needed for torrid heat in July and August. The wine is 100% Sangiovese, whole bunch pressed. Serve it with grilled mahi, or a chilled cucumber/tomato/mozzarella salad. Take it to the pool, the beach, the place most in need of maximum refreshment in your life. — JM

Corzano e Paterno “Il Corzanello” Rosso Toscano IGT

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Round, smooth stones that were once a seabed

Elevation: 300m

Grapes: Sangiovese, Cabernet and Merlot

Method of fermentation: The grapes from the coolest plots are hand picked and cooled. Crushed and destemmed and then cold soaked for about 5 days.

Fermentation is carried out without the addition of commercial yeast at low temperature, between 18 to maximum 22°C. Maceration is very brief, maximum 5 days so as not to extract to much tannins. Malolactic and 5 months of ageing in stainless steel. Bottled April-May following harvest. A fresh, fruity, immediate wine.

Bottles Produced: 5,000 - 8,000

Tasted in April, this wine was quite approachable. Cool fruit, violet, fresh plum. Low in tannin, but nice nervy energy from the mineral/acid component of the wine. It struck me as a really good red for spring and summer, and (unsurprisingly) a great match for pecorino cheeses. — JM

Corzano e Paterno “Terre Di Corzano” Chianti DOCG

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Stony

Elevation: 300m

Grapes: Sangiovese and Canaiolo

Method of fermentation: The grapes are hand harvested and fermented separately by variety and vineyard. In the best years, about 5% of the grapes are not destemmed. Fermentation is spontaneous in small 1 ton bins and open fermentors. Maceration varies between 21 and 35 days depending on quality of grapes, vineyard location and soil. During fermentation and maceration extraction is done by gentle plunging and rarely pump overs. Malolactic fermentation partly in wood partly in steel. Aged for about one year in “Botti grandi” with a capacity of 25 and 40 hl and a small part in used barriques and tonneaux.

Bottles Produced: 30,000

Corzano’s Chianti seems quite delicate. The wine is 90% Sangiovese and 10% Canaiolo. It spends one year in large oak casks and a mix of old barrels. The wine does a 21-day maceration at the start of fermentation, to extract cool, fresh berry fruit, and color. Drink it with carnitas, or a simple spaghetti marinara. — JM

Corzano e Paterno “I Tre Borri” Sangiovese Rosso Toscano IGT

Viticulture: Certified organic

Soil type: Clay/Limestone/Fieldstone

Elevation: 300m

Grapes: Sangiovese

Method of fermentation: The best Sangiovese grapes are selected and hand harvested in the vineyards and again at the cellar.

Fermentation is spontaneous, without the addition of commercial yeasts, in open wood vats and small open 1 ton fermentors. In the best years a small portion of the grapes are not destemmed. Maceration lasts up to 40 days, during which every day gentle plunging of the cap is done manually and only rarely pump overs. After gentle pressing of the skins it completes malolactic fermentation in wood.

It is aged in tonneaux and 25 hectolitres vats for up to 26 months. It is only produced in the best years.

Bottles Produced: 5,000 - 8,000

To me there is no argument: this is the best wine Aljoscha and family produce. There are so many ways that Sangiovese can be outstanding. I Tre Borri takes the path of ripe summer blackberries, just-macerated strawberry, star anise and clove. There’s phenolic ripeness and clarity to the palate-feel. Served cellar temperature it is refreshing on a warm day, in spite of being medium weight with noticeable fine tannins. I want tender pork with i Tre Borri, but valid options abound. — JM

June 4, 2012

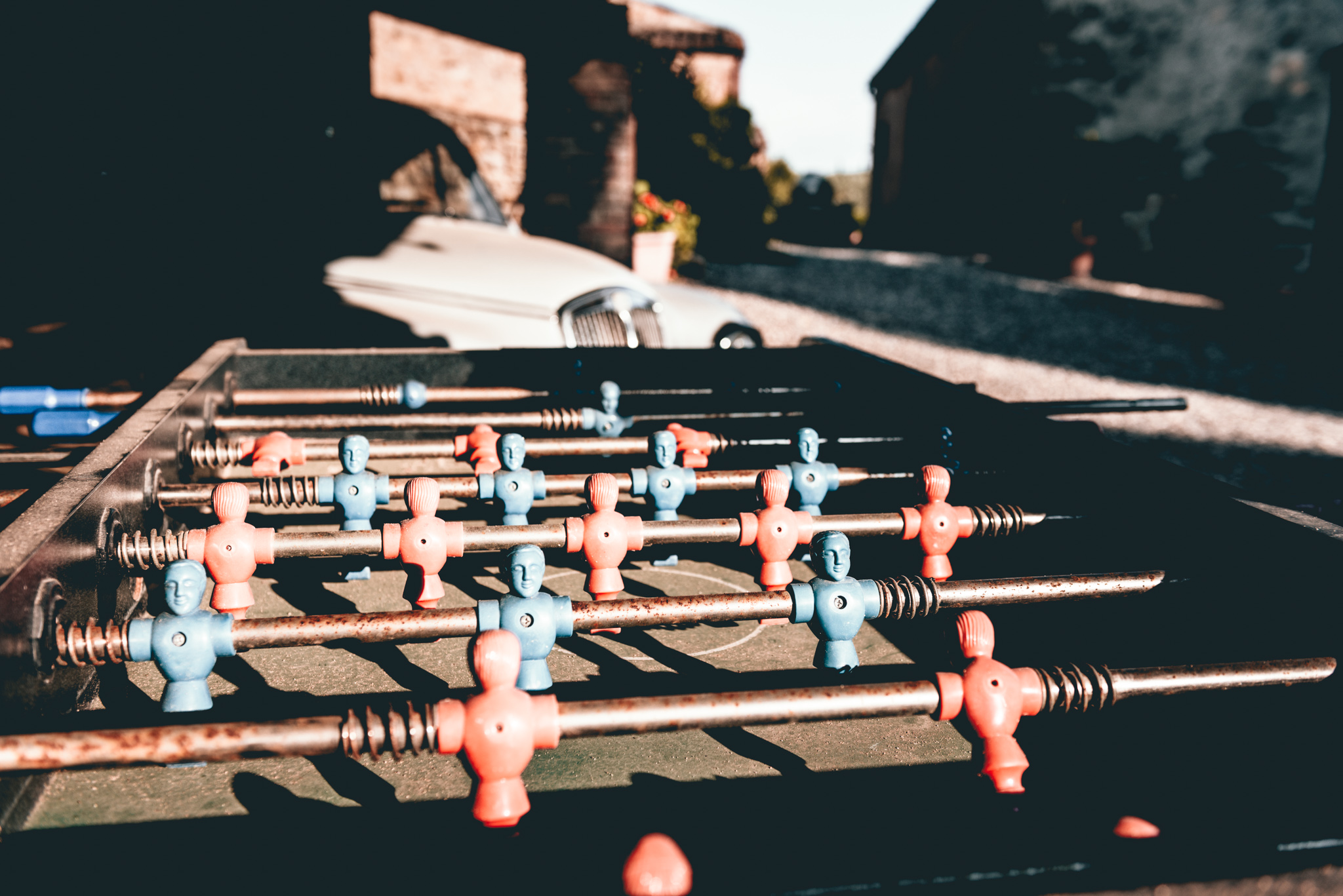

There is a wrong way to get to Corzano e Paterno, and I took it. When I told Aljoscha Goldschmidt about my GPS misadventure he said, “That isn’t even a road for cars.” It was not. I spun through a riverbed of gallestro stones past alarmed German tourists and fishtailed up a nearly vertical hill track mostly travelled by mountain and motor bikes. I arrived at Paterno and met Aljoscha’s kind aunt, who broke the news that the winery had consolidated to the Corzano side of the valley a couple years ago. She resided on the side with the sheep.

When Aljoscha’s uncle Wendelin Gelpke retired from architecture and moved to Tuscany in 1972, he wanted to create a real farm, with animals, grapes, olives, grains: the possibility of a self-sustaining system. He bought Paterno from the Marchesi Niccolini in 1975. They acquired sheep “because cows are too big” and began making cheese. Today they sell a small range of really impressive and diverse cheeses. My favorite is Buccia di Rospo. It began as a mistake in the dairy: now the name is registered, because of imitators making fraudulent versions of their discovery. Today the family keeps 700 milk sheep (and several sheep dogs) at Paterno.

Corzano was added later. The hill faces Paterno across a narrow valley to the southwest of Florence. From Gelpke’s initial 5 ½ hectares the combined property has grown to 17 hectares. Three thousand olive trees take up much of the land, along with hay and cereals to feed the sheep. Forty years ago a fire destroyed some of the estate’s hillside olive groves. The family replanted these excellent south-facing slopes with vines.

Corzano e Paterno practice organic agriculture but are not certified as such. They produce 75,000 bottles of wine annually. They do a double green harvest: a rough one in July, then a finer adjustment later in the season once they have a better sense of the overall character of the weather for the season. “Fifteen years ago the grower with the most courage, the one who picked latest, that person made the best wine.” Goldschmidt said. “But that has changed. The climate has changed. It is now possible to end up with seriously overripe wines.”

At Corzano e Paterno the grapes are hand-harvested and triaged twice on vibrating sorting tables to remove all unhealthy fruit and detritus of harvesting. They sometimes use natural yeasts for fermentation, sometimes a mix of cultured and natural. “The (added) yeasts that begin the fermentation are never the ones that finish it. Yeast from the fields and the cellar always do that. The aromatic profile therefore stays close to the same.”

Corzano e Paterno makes many small experimental batches of wine to test this and other theories. Like what type of closure is best for the ageing of a wine, or if vineyard management strategies affect overall alcohol content. “It’s hard to affect it much.” Goldschmidt stated. “Sugar ripeness is the issue (and that is related to heat). All regions now have the same problem.” He thinks maybe planting some vineyards with different sun exposures may be an option in the future. Sites previous generations would have thought to be too cool or shady.

Corzano e Paterno is a perfect place. All the products show love from two generations of a family working a beautiful land.

When Tilio Gelpke was eight years old he was taken out of school, and a lifetime of working with sheep began. Tilio’s father, a Swiss architect, bought Corzano e Paterno in the late 1960’s. He imported 50 sheep from Sardinia, to clear the land of bushes. Tilio says goats would have been better. Sheep prefer grass, goats like larger vegetation. “Together they make a good team.” Tilio started learning from a Sardinian family that relocated to Tuscany with the initial animals.

We are talking in the middle of a milking parlor. It is loud, aromatic, and a fine balance of order and chaos, similar to watching people get onto a subway train, or file into seats at a large theater. There is bustle followed by placid moments of chewing and the methodical attachment of pumps. The sheep file in and jostle for favorite positions: they don’t like wet spots on the floor. I feel the same way. When an animal with four legs slips, limbs go in all directions its head ends up smacking the concrete. A free two-day-old lamb wanders through the milking in progress, then down to us in the center of the room. It’s amazing how alert and active this little creature is in comparison to barely awake human newborns. They register a similar level of cuteness, in my opinion.

Tilio attaches pumps and checks microchips in the first stomach (sheep have two) with a handheld device to verify identities and record production levels. Today he is the angel of death. Animals that are very old (generally over 12 years,) have malformed teats, or simply do not produce average levels of milk, are marked with a dark green stripe. It is the stripe of imminent slaughter.

“If an old animal dies on the farm I have to pay 50 euros to dispose of it,” he says. “If I only get 10 euros from the butcher… I hate it, I hate dealing with them, I’d rather make illegal sausage on the farm, but the regulations make us do stupid things. People can buy a pig and slaughter it at their property to make sausage, but I cannot do the same with my old animals (without violating EU codes.)

“Fifty years ago there was so much concentration of productive food: it was a garden.” Tilio says everything was grown here, not just olives and grapes. People had to maximize the potential of the land. “Each stone you see, someone has turned it a few times. How far do I have to go back to find an era like this? Probably before the Etruscans.” Across more recent millennia the land had to be more intensively farmed, to support the population density of Tuscany. Tilio says that until the last century 20 people would live on the production of 10 hectares of land, while giving 50% of the harvest to their aristocratic masters. “It was slavery,” he says. But it made people wring every ounce of productivity from their territory. Vines were trellised along fruit tress, and vegetables co-planted between the vines, and anywhere else that wasn’t too rocky or steep.

“Romans had a dependency on grain. Florence could not have had the Renaissance without a greater concentration of crops.”

It is initially unsettling to have a long conversation about the wastefulness of modern Tuscan agriculture surrounded by dairy sheep and pasture land, in a region whose most striking visual characteristics is abundant and often scrupulously cultivated olive groves and vineyards. But Tilio’s point is we must take a longer perspective. “In the 1950’s someone with 50 sheep would have a wealthy family.” His family have 650. His neighbors have productive land planted with olive trees that they do not use anymore, because the labor is too expensive, even to produce valuable Tuscan oil. The way they farm does not support them.

Tilio casts his life as the story of a struggle to regain some productivity for the farm. He built the first stable in 1986. “Corzano e Paterno still has animals because I am stubborn. At first I was also the only salesman for the cheese. The stress and reality of what we were doing first came when they (his cousin Aljoscha Goldschmidt and his partner Toni) had a ton of cheese.”

“My cousin said we must throw it all to the pigs. I threw none away.”

Tilio learned quickly that his market for their farmstead cheese was not the grocery store. “Fresh cheeses lose weight. Retailers don’t like it, which is why they prefer industrial cheese.” Restaurants in Florence were a much better market, able to sell a selection of diverse pecorinos. The dairy thrived, and today they can barely keep up with demand.

Tilio says the he mainly takes issue with the emergence of industrial cheese that tries to look like artisanal cheese. The ubiquity of these products in Italy sounds similar to what you find on a casual grocery store tour in America.

“Cheese makers have no secrets. It’s something we have been making for 10,000 years.” A mistake created their first “signature” cheese, Buccia di Rospo. Instead of tall round pecorinos the cheese came out as squat bloomy disks. The expression Buccia di Rospo was used by Aljoscha to say the cheese was rotting: literally “It’s toading off.”

Tilio also implicates man as the root of problems interacting with the greater environment. Locals complain of the reappearance of the occasional wolf. “We have (problems with) wild animals because agriculture has changed. Wolves follow the wild boar, deer. When I started (working life at Corzano) we had pheasants. Those were the large animals you would see. Now we have wild boar as big as a pig. When you see them on a motorbike I say ‘please, you first.’”

Hunters imported larger boar from central Europe. They thrive in the food-rich fields of Chianti, growing fat on the Sangiovese grapes from vines they vandalize. “When I was a child they were hill animals, small, to get between rows. The Hungarian ones give birth twice a year.” And now they become overabundant.

Tilio has lived through boom and bust years in Chianti. “It’s an Italian disease. When something is working well they can spoil it in a very short time.” I hear this kind of shockingly deprecating language from many farmers working in Italy. “1973 was a terrible vintage and they sold it like it was a normal wine, and killed the market. Then it took many years and someone with money, it was Antinori but it could have been anyone, to fix it again.”

He then gets positive “We learn so much out of growing food.” We are outside, sharing stories of trips to Morocco, cheese making friends in New Jersey, minutae of farm life. A sheep dog wanders between us. “He thinks of himself as equal to us, a peer.” Tilio says, indicating the dog. “I call him but he will not come. But he has a job to do.” I realize I’ve been here a long time, and it’s still not 8am. Time to depart. My work day is starting.

His sister Arianna makes the wine. The way she speaks about it “I am still learning from Joshi,” you’d think it was her first year. She’s been in the cellar since 2004. She was born on the farm, it was her father’s, and her mother still lives at Paterno, close to Arianna and her brother.